In mid-afternoon on 31 July 2016, Frank Clark found a 'Purple Swamphen' on the South Girder pool at Minsmere RSPB, Suffolk (see Frank's finder's account). With no camera to hand, he sought photographic assistance from birders in the reserve's South Hide before alerting the wardens. Fortunately the bird continued to show well at times throughout the afternoon and evening and had been twitched by a crowd numbering into the hundreds by dusk. It continued to show well on Monday morning, but became more elusive during the afternoon, disappearing for several hours. It was still present on Tuesday.

There have been several previous occurrences of 'Purple Swamphen' in Britain, though these have generally related to Grey-headed Swamphen (Porphyrio poliocephalus) of the Middle East, Indian Subcontinent and South-East Asia, a species which is kept in captivity widely across Europe, including in Britain. A record from Cumbria in October 1997 was considered of indeterminate form (Knox et al. 1997; read online here), with mixed opinion over its origins, which were never definitively established. African Swamphen (Porphyrio madagascariensis), breeding widely across sub-Saharan Africa and north along the Nile Valley to Egypt (and also in Israel), is also kept in captivity in Europe and birds appearing to match this phenotype, with extensive green upperparts, have been recorded as presumed escapes across the region.

The Minsmere bird was a uniform blue colour, with slightly paler blue head and entirely blue upperparts, ruling out both poliocephalus and madagascariensis and simultaneously identifying it as a Western Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) of Iberia and the Western Mediterranean — the first confirmed record of this species in Britain.

Western Swamphen, Minsmere RSPB, Suffolk, 31 July 2016 (Craig Shaw).

Western Swamphen, Minsmere RSPB, Suffolk (John Richardson).

Though the prospect of an escapee must always be considered with any potential addition to the British list, this taxon appears to be comparatively rare in captivity across Europe and is possibly kept no closer than Germany (see here and here; the two British collections in the latter link report all their captive swamphens as present and correct). Breeding as close as southern France, its prospects as a genuine vagrant here are much higher than the previously recorded Grey-headed, so drawing comparisons between past British records of that species and the current individual should be avoided.

Escaped Grey-headed Swamphen, Saltney, Clwyd, 1 August 2010 (Rob Smallwood).

The modern-day presence of the genus Porphyrio across the Old World and Oceania demonstrates its ability — both past and present — not only to travel great distances and to colonise vast swathes of land, but also to make significant sea crossings. Rails and crakes repeatedly prove themselves to be far more capable fliers than birders give them credit for; their almost cumbersome flight action belies their ability to travel great distances and consequently perform some of the most spectacular vagrancies known among any landbirds. When considering the genus's history, crossing the English Channel or southern North Sea from continental Europe to East Anglia would theoretically represent a relatively minor obstacle for a dispersing Western Swamphen and should not be considered a reason to count against it being a genuinely wild bird.

However, the most convincing argument for wild origin is the exceptional northward dispersal observed in France in 2016, some French birders even forecasting that a British record might be imminent in the days leading up to the discovery of the Minsmere bird. Further details of these birds, including the most northerly recorded in France in modern times, can be found below.

Adult Western Swamphen, Minsmere RSPB, Suffolk, 1 August 2016 (Video: Pete Hines)

Taxonomic background

Several English names have been attached to the Minsmere bird, so to avoid confusion here we clarify the current taxonomic position of Western Swamphen according to the International Ornithological Congress (IOC).

Following the split of African Swamphen several years ago, the IOC split the remainder of the Purple Swamphen complex into several species in July 2015. This saw Porphyrio porphyrio renamed Western Swamphen (from Purple Swamphen) and Grey-headed Swamphen elevated to full species status. The complex now forms six species, with the three additional taxa as follows:

- Black-backed Swamphen (Porphyrio indicus) of South-East Asia to Greater Sundas and south-west Sulawesi;

- Philippine Swamphen (Porphyrio pulverulentus) of the Philippines;

- Australasian Swamphen (Porphyrio melanotus) of Australia, New Zealand, and Oceania.

Current status of Western Swamphen in France and an exceptional dispersal in 2016

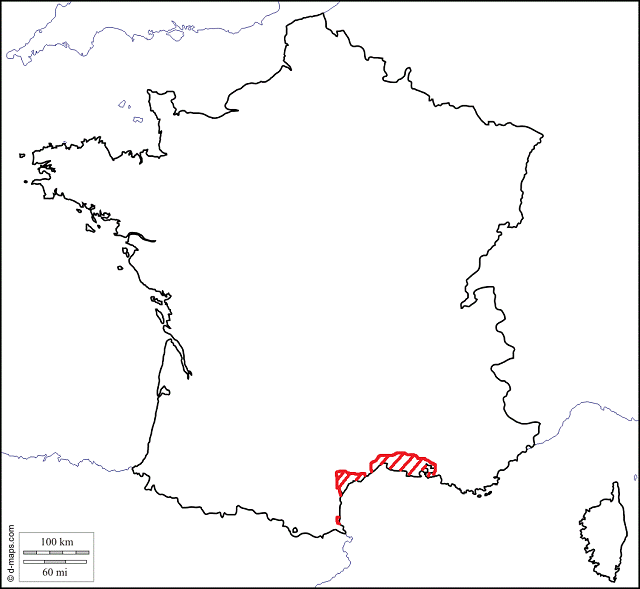

In the 19th century, Western Swamphen bred only along the Mediterranean coast of Spain, as far north as the Pyrenees, and it was considered an occasional visitor to France (Sanchez-Lafuente et al. 1992), with records from the départements of Gironde, Dordogne, Vendée, Eure, Seine-Maritime, Somme, Aisne, Finistère and Nord (Dubois et al. 2008).

Reintroduction programmes in Spain in the late 1980s put an end to the decline observed throughout the 20th century (Mathevet 1997; Flitti 2015) and observations of Western Swamphen became more numerous on the Mediterranean coast of France in connection with the positive population dynamics observed in Catalonia. The first breeding record in France was on a pond at Canet-en-Roussillon, Pyrénées-Orientales, in 1996 (Aleman 1996; Cambroni 1996).

The species continued to increase gradually (Gonin 2003), but then expanded its breeding range quite dramatically in 2006–07, colonising the départements of Gard, Hérault and Bouches-du-Rhône (Chantelat 2006; Flitti 2009). The number of breeding pairs increased from 26–42 in 2006 to 90–123 in 2011 (Quaintenne 2013).

The spell of cold weather at the end of February 2012 caused significant mortality, with dozens (perhaps hundreds) of corpses found locally and dying individuals also noted at many sites. The species became rare in its historical stronghold of the Eastern Pyrenees and Narbonne (Flitti 2015). The eastern periphery of the French population was also affected and it became quite rare in Camargue and the Vigueirat Marshes. The breeding population crashed to just 13–29 pairs in 2012 (Quaintenne 2013).

A spell of freezing weather in February 2012 wiped out large numbers of Western Swamphens in southern France; many corpses were retrieved and the birds were found to have starved (Photo: Jean-Pierre Trouillas)

A new wave of expansion on the Mediterranean coast began in 2014, again in the east. A significant increase in sightings was noted and a number of the sites occupied before the cold weather of 2012 were recolonised. The breeding range expanded rapidly, with significant numbers again noted in Camargue, at Étang de Berre and in the département of Hérault. The species also began to show a slow population increase in its historical range of the Eastern Pyrenees, with a few instances of nesting observed in 2016. Summer is the best time to observe the species, when water levels are low and individuals come out of the reedbeds to feed.

Interestingly, in the Aiguamolls de l'Empordà Natural Park, one of the sites of the Spanish reintroduction project, Western Swamphen has become very rare and research is being conducted to determine the reasons for this negative trend.

French distribution of Western Swamphen during the 2016 breeding season.

As well as the strong positive populations trends observed along the French Mediterranean coast in the past two years, 2016 produced an exceptional number of individuals observed well to the north of the breeding range. It is suspected that these are the result of good breeding seasons and the absence of a particularly cold winter (February 2012 aside) for many years, rather than drought as is often cited. Details of each record can be found below:

- Adult, Bruch, Lot-et-Garonne, 11–25 April;

- Adult photographed, Arnas, Rhône, 22 May;

- Adult photographed, Châteauneuf-du-Rhône, Drôme, 23 June;

- Adult, Etang des Aulnes, Bouches-du-Rhône, 28 June;

- Adult, Cambounet-sur-le-Sor, Tarn, 1 July;

- Adult near Marnay, Saône-et-Loire, 2 July; joined by a second individual a few days later;

- Adult, La Capelle-et-Masmolène, Gard, 16 July;

- One, Étang de Beaurepaire, Deux-Sèvres, 19 July;

- Adult, Guidel, Morbihan, 20–31 July at least.

- Adult trapped and ringed, Creys-Mépieu, Isère, 22 August

- Adult, Les Bréviaires, Yvelines, 5–7 November

Two Western Swamphens, Marnay, Saône-et-Loire, July 2016 (Photo: Bernard Fontaine)

Western Swamphen, Guidel, Morbihan, July 2016 (Photo: Marc Galludec)

Note that a swamphen of unknown origin (unringed and able to fly), was observed from 10 December 2014 – 18 November 2015 in Teich, Gironde (44.6449, -1.0098). With its green-washed upperparts, this individual is suspected to be an African Swamphen.

Apparent African Swamphen, Teich, Gironde (Photo: Nicolas Warembourg)

Conclusion

Given the recent rapid increase in the core population on the French Mediterranean coast since the cold weather of 2012 and the exceptional series of out-of-range birds across France this spring and summer, we believe that there has never been a better year for a vagrant Western Swamphen to appear elsewhere in north-west Europe — at least in modern times. While considerably further north than any other records so far in 2016, the appearance of an adult at Minsmere, Suffolk, fits closely with the observed pattern of vagrancy across France this summer, which has seen birds recorded as far north as Brittany. Furthermore, Western Swamphen appears rare in captivity across Europe with none currently known to have escaped in Britain. We are of the opinion that, unless strong evidence emerges to suggest otherwise, the Minsmere Western Swamphen should be considered a wild bird and therefore a new addition to the British avifauna.

References

Aleman Y. 1996. La Talève sultane Porphyrio porphyrio, une nouvelle espèce nicheuse pour la France. Ornithos, 3 : 176-177.Cambrony M & Aleman Y. 1996. Confirmation de l'implantation de la Talève sultane Porphyrio porphyrio dans le département des Pyrénées-Orientales. Alauda, 64 : 443-445.

Chantelat J C. 2006. Un pas vers l'est : l'étang du Scamandre (Gard), nouveau site de nidification de la Talève sultane Porphyrio porphyrio en France. Alauda, 74 : 274.

Dubois P J, Le Maréchal P, Olioso G & Yésou P. 2008. Nouvel inventaire des oiseaux de France. Delachaux et Niestlé, Paris, 559 p. Flitti A, Kabouche B, Kayser Y & Olioso G. 2009. Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs de Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur. LPO PACA. Delachaux-et-Niestlé, Paris, 543 pp.

Flitti A & Clément D. - Talève sultane, in Issa N & Muller Y coord. (2015). Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs de France métropolitaine. Nidification et Présence hivernale. LPO/SEOF/MNHN. Delachaux-et-Niestlé, Paris.

Gonin J & Clément D. 2003. Statut de la Talève sultane Porphyrio porphyrio dans l'Aude et en France en 2002. Ornithos, 10 : 252-257.

Knox A, Melling T & Wilkinson R. 2000. The Purple Swamp-hen in Cumbria in 1997. British Birds 93: 442-445.

Mathevet R. 1997. La Talève sultane Porphyrio porphyrio en France méditerranéenne. Ornithos, 4 : 28-34.

Quaintenne G & Les Coordinateurs Especes. 2013. Les oiseaux nicheurs et menacés en France en 2012. Ornithos, 20 : 297-332.

Sanchez-Lafuente A M, Rey P, Valera F & Munoz-Cobo J. 1992. Past and current distribution of the Purple swamphen Porphyrio porphyrio L. in the Iberian Peninsula. Biological Conservation, 61 : 23-30.